If you’re a new subscriber to Culture Café (and I know there are quite a few of you) welcome, welcome, welcome! I would like to say that Culture Café is a warm and cosy place, where everything is lovely and safe and calm. I can’t, of course, because that would require us all to have lobotomies and the waiting lists for those are probably quite long. What I can say is that Culture Café is a place where we pay attention to beauty as well as to (sometimes painful) truth.

And that, to be honest, is what’s been holding me up. The “truth” has been so awful that I haven’t been able to concentrate at all.

I’ve been planning for a couple of weeks to write about Jane Austen. It’s the 250th anniversary of her birth. To mark it, the BBC released a new costume drama called Miss Austen. Lovely, I thought, when I heard this. Just what we need. Bring on the bonnets!

The “Miss Austen” of the title is, of course, not Jane. Anyone who knows their (English etiquette) onions knows that that title would only be given to the eldest unmarried daughter, who wasn’t Jane. “Miss Austen” was Cassandra Austen, Jane’s beloved sister and companion until her death.

The TV drama Miss Austen takes place after it. Based on Gill Hornby’s novel of the name, it’s a re-imagining of the events surrounding Cassandra’s rescue, and destruction, of most of Jane’s letters. Hornby lives, with her husband, the author Robert Harris, in Kintbury in Berkshire, in a house built on the site of a rectory that was once the home of some of the Austens’ closest friends. The second son in that family, Thomas Fowle, was a former pupil of Jane and Cassandra’s father. In 1794, Cassandra became engaged to him. Needing money to marry, he went on a military expedition to the Caribbean as chaplain to his cousin, General Lord Craven. He died of yellow fever in 1797.

Keeley Hawes plays Cassandra with understated grace. Her quiet stoicism, when she hears of Fowle’s death, is more moving than any outburst. In Hornby’s re-imagining, Cassandra has promised Fowle that she will never marry anyone else. When she turns down a second marriage proposal, from someone she is clearly deeply attracted to, I felt sad, as I was meant to. But if she had accepted it, we might have missed out on the real love story, which is the one between Cassandra and Jane.

Cassandra, at least in the drama, believes Jane won’t cope without her. In any case, she doesn’t want to be without Jane. When Fulwar Fowle, Thomas Fowle’s elder brother and the husband of Jane and Cassandra’s friend Eliza, dies, Cassandra rushes to Kintbury to support Eliza but also to find and destroy Jane’s letters to her. I don’t think anyone thinks she did this because Jane was living a secret life of wild excess. No, she did it because she knew Jane wanted to be remembered for her work, not her life.

And she is. In an age when people vomit out the minutiae of their lives on social media, there’s something majestic about a life that offers us little to scavenge on except bare bones. The novels stand. My God, they stand. Works of towering genius that will endure until the planet has burnt.

As a child, I watched every TV adaptation. As a family, we would often visit Jane Austen’s home in Chawton, Hampshire and have a cream tea at Chawton House, the Elizabethan manor house once owned by her brother, Edward. Like every other English-literature-loving teenager, I gulped down Pride and Prejudice and then spent decades looking for Mr Darcy. In the end I found my Mr Knightley. He is, of course, a much better bet.

It's no coincidence that the key love interest in the first Bridget Jones book, and the shadow hanging over the others and the latest film, is a man called Darcy. He is rumoured to have been inspired by a young human rights lawyer called Keir Starmer. Yes, it is all getting rather surreal.

I enjoyed Miss Austen. I liked the acting, the script, the costumes and the settings but what I really, really loved was the interiors. Stick me in a Georgian house, with wide-plank wooden flooring, an elegantly curved staircase and soft yellow walls, and I’m in heaven. All my life, I’ve dreamt of living in a Georgian townhouse. In 2023, when my Mr Knightley and I were looking to buy somewhere together, he sent me a listing of a house that had just come on the market. “Jane could have lived here” was the heading of the email that flashed up on my screen. When I looked at the photos in the listing, I could only agree.

I fell in love with that house as soon as I saw it. It was the first thing I thought about in the morning and the last thing I dreamt of at night. Friends joked that they would have to put on muslin frocks to visit us. I imagined us all sipping dainty cups of tea as we gathered round a piano. When the purchase fell through, I felt a flicker of what Cassandra must have felt when she heard the news about Thomas Fowle. Unlike Cassandra, I soon found a replacement. Victorian, but we painted the sitting-room yellow.

What struck me, watching Miss Austen, was that the elegant interiors, outfits and manners were all symbols of a much bigger theme. I had thought, when I first read them as a teenager, that Jane Austen’s novels were all about romance. That features, of course, though I’m not sure that any declarations of love match Cassandra’s letter to Jane’s niece, Fanny Knight, after Jane died. “I have lost,” she wrote, “a treasure, such a sister, such a friend as never can have been surpassed. She was the sun of my life, the gilder of every pleasure, the soother of every sorrow.”

The “sun of my life”. I think most of us would settle for that.

No, the real theme, the one I never really noticed when I dreamt of finding Mr Darcy, is money. Money and what it buys you, which is freedom.

In Jane Austen’s novels, as in most societies throughout history and many still today, women seek husbands so they will have a roof over their heads. Marriage is a transaction. It may or may not involve affection, sexual attraction or what we call romance. It will almost always involve property, or at least access to a home. The terms of the transaction will depend on the wealth of the parties involved and the balance of power. It is, in other words, all about the deal.

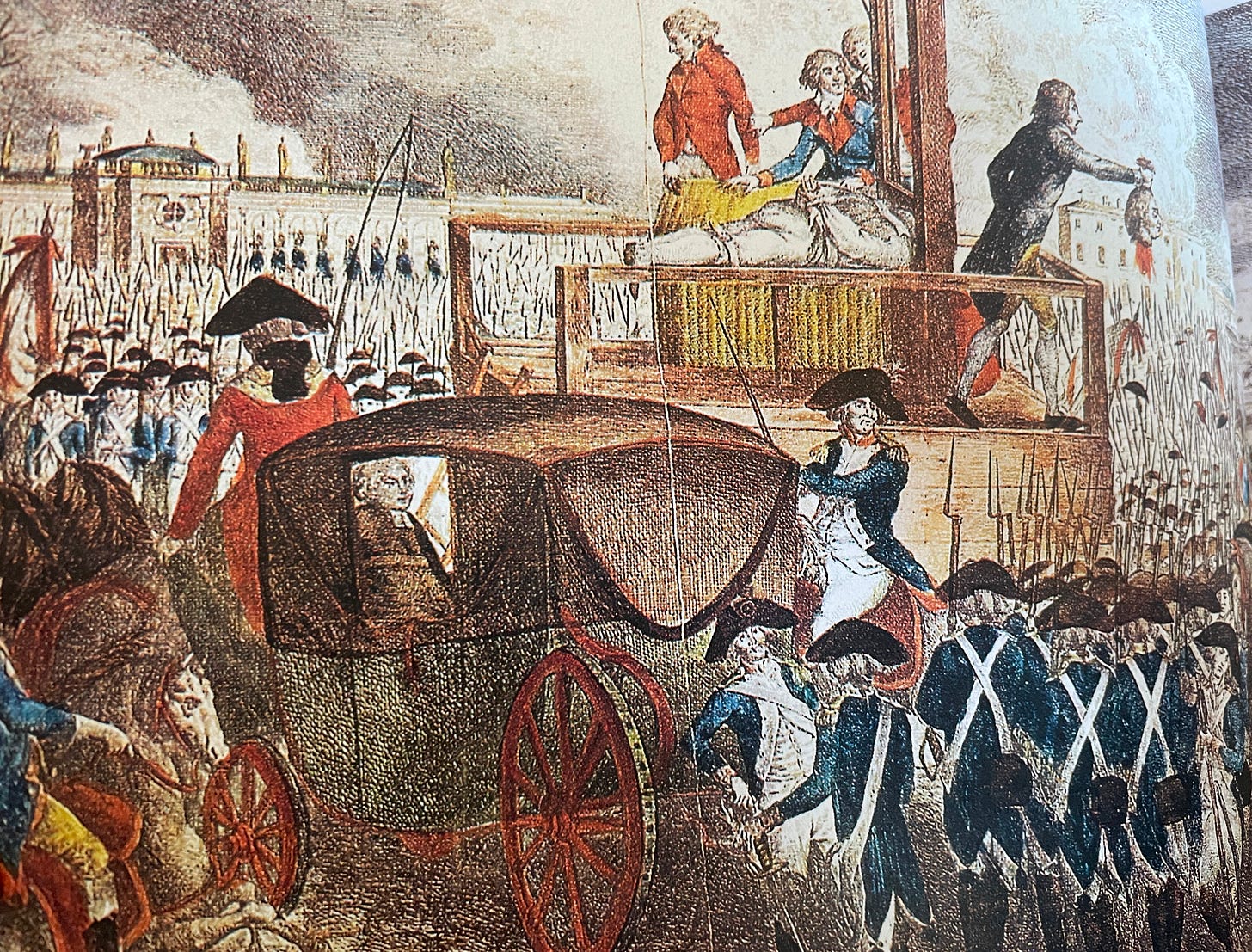

We don’t know what Jane Austen thought about the geopolitical background to her life. We don’t know what newspapers she read or how far she and Cassandra talked about the bigger historic picture. We do know that many of her characters, and several of her brothers, were either in the army or the navy. Great Britain was a great naval power. Jane was eighteen when her cousin Eliza’s husband, Jean-Francois Capot de Feuillide, was guillotined in the French Revolution. She was 23 when Napoleon Bonaparte seized power and launched a series of wars. She was 27 when Britain declared war on France. She died two years after the Napoleonic Wars ended with the Battle of Waterloo.

We don’t know how much she knew about the battles and the gore. We do know that about 300,000 British soldiers died in the Napoleonic Wars and that all young women would have noticed the shortage of young men.

Jane was born in 1775. That was the year that George Washington became Commander of the Continental Army in the American Revolutionary War. On 4th July the following year, in what’s now Manhattan, he was preparing for battle when a Declaration of Independence was released in Philadelphia. That declaration was the founding document of the United States of America.

I am pleased, for Jane’s sake, that she did not have a constant stream of notifications on her various devices about the latest developments on all these fronts. Perhaps she wouldn’t have written her novels if she had. She may not have known all that much about the power struggles in Europe and America. She may not have known, or noticed, which man was claiming which state, throne, office or country on which month or day. It may have been enough for her to note which man was asking which woman for the next quadrille.

I am not sure how Jane would have felt if she had discovered that the nation created by that declaration of independence from her own country had gone on to become the most powerful nation in the world. Since she was intensely aware of the link between power and money, she might have been intrigued by its founding premise that “all men are created equal”. Perhaps she would have been pleased that that powerful country went on to help her own country beat a fascist dictator in a world war.

I am certainly pleased. We might all be greeting each other with Nazi salutes if it hadn’t.

I don’t know how Jane Austen would have felt if she had been glued to her devices this week. If, for example, she had learnt that the leader of the United States had called the democratically elected leader of a country that had been invaded a “dictator”.

I don’t know how she would have felt if she had learnt that that country had voted with the aggressor in a UN resolution.

Or if she had learnt that key advisers to that country’s president had re-introduced the Nazi salute.

Or if she had learnt that that country had been trying to blackmail the country that had been invaded into handing over precious resources in exchange for – well, absolutely nothing.

Or if she learnt that the leaders of that country had been trying to bully the leader of the country that had been invaded into giving up its land, its minerals and its future, with no security back-up at all.

I don’t know how Jane Austen would have felt if she had seen what happened in the Oval office on Friday: two men behaving like mafia bosses trying to bully the bravest leader in the world.

I can only tell you how I felt: sick to the bottom of my stomach. And that’s how I feel now.

Unlike Jane Austen, I have lived in a country that has been at peace for eighty years. Although I have often disliked its presidents and its politics, I have assumed that the United States of America was broadly aligned with the vision and values of Europe: values that relate to democracy and the rule of law. I thought we had an agreement to keep those values, and our countries, safe. I thought we had a deal.

If we did have a deal, that deal has been broken. The leader of the United States of America is on the side of dictators. He said he would become one and people thought it was a joke. It wasn’t. It isn’t. He has threatened to take land and supports Vladimir Putin, who has already taken land and wants more.

I am truly grateful for what we had, but it’s over. That world order is over.

“The welfare of every nation depends on the virtue of its individuals” said Jane Austen in her early story “Catharine”. She didn’t say what happens when a country has been taken over by bullies, cowards and fascists who are happy to threaten global security, but we are seeing it now. If you’re not feeling sick to the bottom of your stomach, you should probably check your pulse.

Indeed. It’s been a rough week over here, couple more of my friends got fired from federal jobs, and another is deciding to leave the military as she was asked to do something that went above her red line (we all have points we won’t cross and one thing I advised my friends in the government to do was figure out what they were now, rather than it was too late and they were coerced into stuff they wouldn’t want to do. She told me she was grateful we had discussed it beforehand).

On Thursday we had the opening night of the DC Irish Capital Film Festival and the special guest was former human rights commissar Mrs Robinson (as there was a documentary about her. She is great and an inspiration. I thought the documentary could have been better). In the Q&A afterwards she talked about how dark things appear now, and how she recalled asking Desmond Tutu how he remained so cheerful in such dark times he had been through. “I am a prisoner of hope” he told her, along with kindness and love are the things that will eventually defeat the darkness. It’s a message I gave my own staff on Friday as we were all feeling a tad down after that press conference, and it seemed to help. I think we are all prisoners of hope at the moment.

If Jane Austen taught us anything, it’s that power and money decide everything—including who gets a happy ending. And watching the White House roll out the red carpet for despots, I can’t help but think: would she have even been surprised? She wrote about survival in a world where women had to marry for security, where fortunes were built on inheritance and deception, and where dignity was always at the mercy of power. The parallels are hard to miss.

But if Austen’s heroines were forced to navigate the rigid social contracts of their time, today we’re watching the collapse of the last real contract the West had left: the idea that democracy and rule of law actually meant something. I read this and thought about Afghanistan—how quickly alliances break down, how power bends to convenience, how betrayal is always packaged as pragmatism.

The West loves its grand ideals, but in the end, it always comes down to a transaction. And right now, the deal has changed. Ukraine is being told to settle for scraps. Dictators are being appeased. The message is clear: if you’re on the frontlines of a fight for freedom, don’t expect anyone to stand by you for long. Jane Austen understood that security was always a negotiation.