START HERE! On the slow death of journalism - and the fast death of my career

Why I'm (finally) all in here

Eleven and a half years ago, I lost my job. As I write those words, I feel a sense of shame. Yes, I know it happens to people all the time. Yes, I know many people say redundancy was one of the best things that ever happened to them. Good for them. Bully for them. For me, it was one of the worst.

I had lost half my family, struggled with illness in my twenties and had cancer twice, but losing my job hit me harder than anything had hit me before. I felt as if the house I had been building all my life had been burnt down. I felt as if my tongue had been cut out.

Drama queen? Perhaps. Ancient Mariner? Probably. I do sometimes feel as if I’m wandering around with an albatross wrapped around my shoulders and my neck. The albatross is a relic, a spoil of a battle that has been raging for a couple of decades and that’s raging even more fiercely now.

It’s the war against journalism and against those of us who have been lucky enough to work in it.

I will never forget the thrill of my first byline, in the TLS. I was 26. I was working on a programme of literary events, supporting and presenting writers. I dreamt of having a staff job as a journalist, but for thirteen years I did freelance journalism on top of full-time jobs.

I was 39 when I was invited to apply for the job of deputy literary editor at The Independent. My new boss was an expert on world literature, but also on politics and ideas. Within weeks of arriving, I felt new worlds open up.

Within weeks of arriving, I also found a lump in my breast.

Three years after my sister died and a year after my father died, a man in a smart suit told me the lump was malign.

I had two operations, five weeks of radiotherapy, a hormonal therapy that made me feel sick and giddy, and, in a year of treatment, just two and a half weeks off.

I was on my own and had to pay the bills. Without work, I couldn’t. Work was what I had, what I had built, in long days, long nights and weekends, hunched over my desk. Work was my lifeblood, my oxygen. Writing, reading, words on a page, words on a screen, words marching in battalions or dancing, at the pace of a salsa or a waltz. This was what kept me going, what kept me sane. Words are what make me feel like me.

When the editor told me I was going to be a full-time writer and columnist, I felt as if I had been given the Nobel prize. I had to find a “big name” writer, artist, actor, rock star or politician to interview every week. I had to fix the interview, do the research, read the books they had written if they had written them, travel to the interview, do the interview, transcribe the interview and write it up. I also had to write a column on the biggest issue in the news twice a week.

There were times when it felt like a kind of hell. There were more times when it felt like a kind of heaven.

Six years after I got the “all clear”, the cancer came back.

Three years after the surgery for that, I got a letter about “integration” and “synergies”. The “synergies”, the letter said, would “reduce costs”. The “costs” were people like me.

I was terrified by the prospect of losing my job - my rock, my pride, my joy - and about losing my ability to pay the bills.

But the thing that winded me, the thing I have not, if I’m honest, fully recovered from, was the fact that the young man who took over my boss’s job decided to scupper the contract for a column I had been promised, which I’d hoped would sugar the pill.

The contract was for peanuts. It would have helped in the Wild West of freelancing and its pitiful rates. But it wasn’t losing the money that upset me most. It was losing the readers.

For years, readers wrote to me about their hopes and fears. They told me when I’d said something they had thought but never said. They told me when they agreed with me. They told me when they didn’t. When I had cancer, many of them sent cards and even presents. Those readers cared as much as I did about what was happening in this country and in the world. Those readers made me feel less alone.

In one moment, one whim, one email from a young man in a hurry, they were gone.

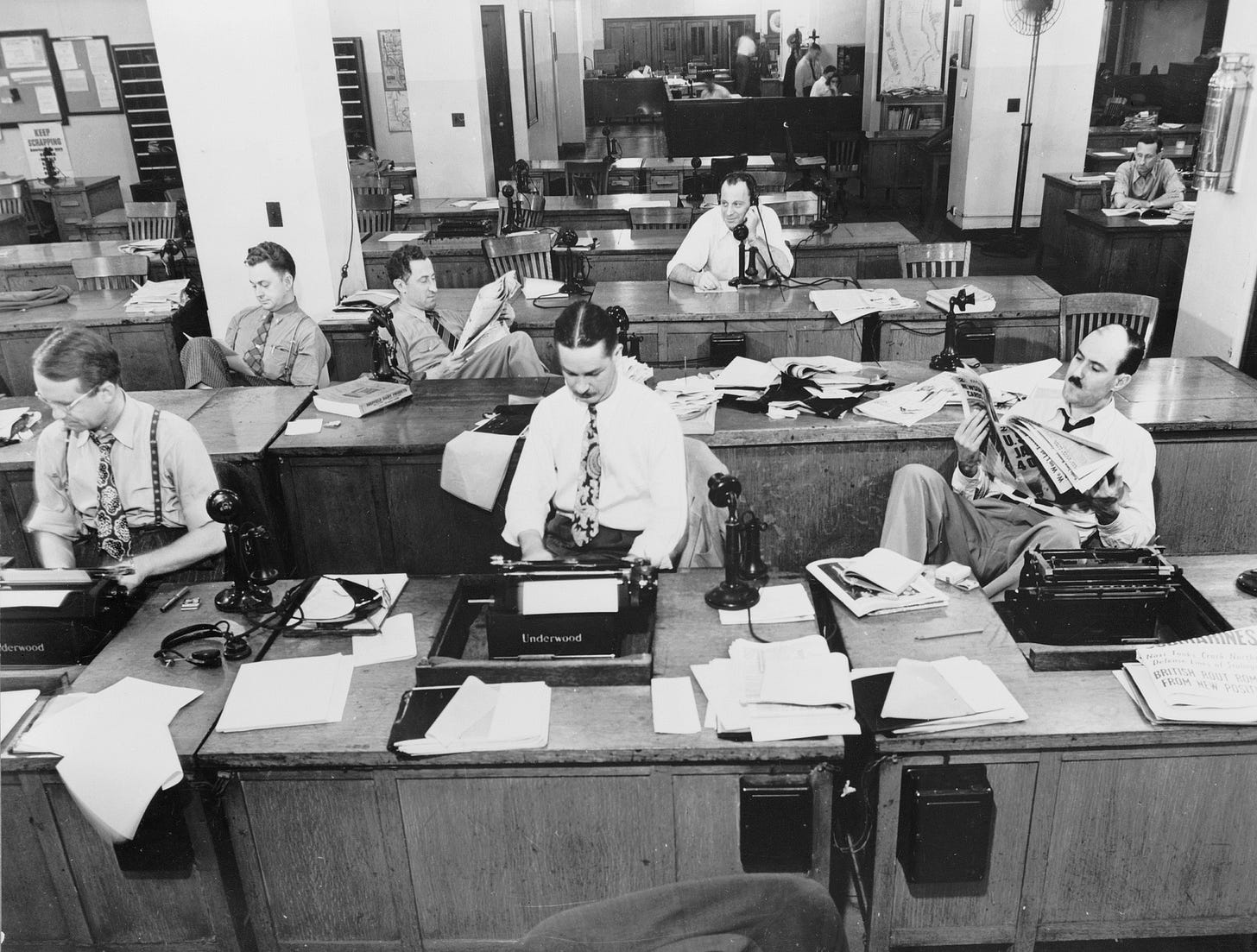

The thing about losing your job as a journalist is that you know you’re not very likely to get another one. Last year, about 8000 journalists lost their jobs in the UK, US and Canada. The internet has been brutal to journalists. Social media is about algorithms. It pushes the controversial, the contrarian, the polarising. It doesn’t care about fine writing, argument, or nuance. It just wants to keep eyeballs on “content” and it doesn’t care if that “content” is produced by a human or a bot.

I think, in the past two weeks, we have seen where this leads.

If you lose your job as a journalist, no one is going to be queueing up to take you on, particularly if you’re edging towards 50. Your main option is to cobble together a living as a freelance journalist. The average pay for freelance journalists in the UK, according to the Press Gazette, is about £27,000. Many earn much less.

(The young man who took over my boss’s job, and who has since flown much higher, now earns about £315,000.)

In my early years as a freelancer, I worked like a demon to pay the bills. And I wrote a book, The Art of Not Falling Apart, partly about losing my job, because sometimes “not falling apart” is the best we can do. By doing a mix of things, I have managed to pay my bills. I do some journalism, here and there. I talk about current affairs on Sky News. I do the odd book review and feature. But oh my God, I miss the act of communion that is writing regularly about what’s in the news, what’s in the air.

On and off, in my freelance years, I’ve written newsletters or blogs about politics, Brexit, life. I’ve written them because I’ve felt I would burst if I didn’t write about these things, but I’ve also felt myself seethe with resentment. It was Dr Johnson who said: “no man but a blockhead writes, except for money”. All journalists feel this in our hearts. Asking us to write for free is like asking an electrician to rewire your house in exchange for smile.

But in a world where so much change is bad, there has been a new kid on the block that has brought hope even to me.

I didn’t really understand what Substack was when I moved my old Mailchimp newsletter here three years ago. I’ve continued to produce sporadic offerings, torn between resentment and the ache to do what I used to do, which gave me such joy: to write, regularly, about what interests me and hope it strikes some chords.

Doing this is what makes me feel alive. It is, in the end, as simple as that.

Over the past few months, I’ve found myself falling in love with Substack. I got an email a few weeks ago telling me that over the summer I read nearly a million words on here. I subscribe to lots of newspapers and magazines, but some of the writing on here is in a different league. Here, you will find some of the best writers in the world. Writing that wakes you up, makes you laugh and makes you think.

So I’ve decided to stop standing on tip-toes on a cliff and dive into this ocean. I’ve decided to call my Substack “Culture Café” because that, for me, is what it’s all about: how we live, how we make sense of this big, bad, beautiful world. Ideally, with a negroni in our hand, in a bar in Florence or Rome.

Culture is the texture of our daily lives, the ideas and politics that shape them, the art and books that light them up. Culture is the coffee and cake and geopolitics. It’s the Bach cello concertos and the White Lotus knock-offs and the party conferences and the Vermentino and the Kettle Chips. That’s what I’ll be offering, in a column, an essay, a cultural snippet or smorgasbord, at least once a week.

For now, at least, I won’t be putting any of my content behind a paywall, but if you’d like to support my work with a subscription, it would show me that you value what I do.

On the 5th November, the world changed. These are dark, dark times. Journalism is under threat. Free speech is under threat. In the US, democracy itself is under threat. And what happens in the US tends to ripple through the Western world.

I can’t control what happens in America. I can’t control what happens anywhere except in my head, heart and home. But while I can write, I will write. I will continue to seek beauty, truth and joy. I hope you’ll join me in that quest, here at Culture Café. Help yourself to something delicious. Let’s raise a glass.

Great to see you on here Christina. I have been where you are now, in fact I am still there - worrying about how to pay the bills looking at a future that looks less than promising. But I have discovered that the main thing is to write, whoever reads it. It stops you falling apart. Looking forward to your posts.

I’ve always loved the way you write about your readers, and as one of them I felt it keenly when you were booted out of “my” paper by that man. I refuse to believe that was 11 years ago!! (Can’t help but think if quality writing and journalism had somehow been better protected and preserved over that time things might have been a bit less horrendous as well)