I met Rob on my way back from a bad date. I was feeling hungry and depressed.

The man I’d just met had a sulky face and cold eyes. He hadn’t asked me any questions. He hadn’t suggested we eat anything. When my bus got to the Elephant and Castle, I decided to stop off for some rice and peas. I was about half way through the queue when a tall man in a leather jacket strode up and asked me if I wanted to go for a drink.

I still can’t really tell you why I said yes. It was something about the set of his shoulders. It was something about the gap between his teeth. He looked as if he could beat anyone in a fight. It turned out he he’d had plenty of practice. Not because he wanted to, but because the fighters at his school in Peckham took one look at him and saw a challenge. In those circumstances, you sink or swim and Rob had learnt to swim.

There was a sweetness in his face. When he smiled, it softened. His eyes laughed and you wanted to laugh, too. Or perhaps I should say: I wanted to laugh, too. Rob’s eyes and smile and face and laugh made me feel happy. I felt as if I had reached a sunny meadow after crawling through mud.

The Elephant and Castle in 1998 was not much like a sunny meadow. Nor was The Old Gin Palace in the Old Kent Road. I can’t remember what we drank or talked about. But I remember the moment he leaned forward and kissed me and the shock of feeling: this place here, with this person, is right.

A few days later, we went to the Notting Hill carnival. There were tens of thousands of people there, but Rob kept slapping hands with people he knew. He had, he told me, lived for some years in a squat in Notting Hill. Some of his friends refused to cross the river to visit him. If you lived sarf, you didn’t go norf. But his dog did. His beloved dog, Satan, still lived with Rob’s parents in their council house in Walworth but would get the Tube on his own to come and visit him.

I wouldn’t have believed this from anyone else, but from Rob I did. Satan used to ride on the back of Rob’s motorbike. When Satan bit Rob, Rob bit him back and Satan never bit him again. Once, Satan disappeared for weeks from Rob’s parents’ house and was tracked down in a nearby tower block. Satan had acquired a girlfriend. “Oh, you mean Blackie!” said the guy who was putting him up, with his own lovelorn pet. Eventually, Satan was lured back to Rob’s parents’ flat. Years later, I remember the phone call Rob made to the vet when Satan was riddled with cancer. We were in the shared garden of my block of flats. Rob had to spell the name out to the vet who was going to put him down. “S – A – T – A – N!” he almost shouted. It was the only time I saw him cry.

When I met Rob, he was living in a double-decker bus in the South of France. I was 34. He was 32. He had already had an extremely eventful life. He had boxed for the Lynn, a boxing club in South London and never lost a fight. He had won medals in athletics and swimming and had a black belt in Wado-ryu. He hated violence, but it followed him. One of his best friends had been shot and killed in a gang-related crime. He had himself had a spell in a young offenders’ institute. (He told me he was framed by the police for this particular incident and I believed him then and believe him now.)

Afterwards, his mother, a Jamaican matriarch who inspired fear and love in equal measure, took him in hand. “This will sort you out,” she said, as she packed him off to stay with his cousin Doug in one of the projects in the Bronx. Doug was, in Rob’s words, “built like a brick shithouse”. After several months surrounded by crack dealers and gun runners, Rob came home determined to stay on the straight and narrow. Which, as far as I know, he did.

He trained as an electrician. He did a degree in music at Goldsmiths and got a first. (I had no idea that he’d been to university, until, years later, I heard him mention it to a friend.) When his friend died, he followed a French girl to a village in Provence. Within a few months, he was fluent in French. He taught music to local youngsters and worked in a bar. Once, he played drums with Stevie Wonder. He had been playing drums since he was four and was, in his words, a “shit-hot drummer”. The band’s drummer was sick and Rob stepped in.

I’m still not entirely clear what brought Rob back from France or if I played any part in it. Whatever was between us remained undefined. Were we together or were we not?

I don’t think either of us knew.

I found out one night that his friends called me “Fluffy”. It was a kind of shorthand for “posh bird”. It made me laugh, because fluffy I am not. To my friends, he was always just Rob: the man who would stride into a room and own it.

Rob was working as a barista at Caffè Nero in Frith Street when the nail bomb went off at the Admiral Duncan. He helped pull people out from under the rubble. When he got to my flat, there was blood on his jeans.

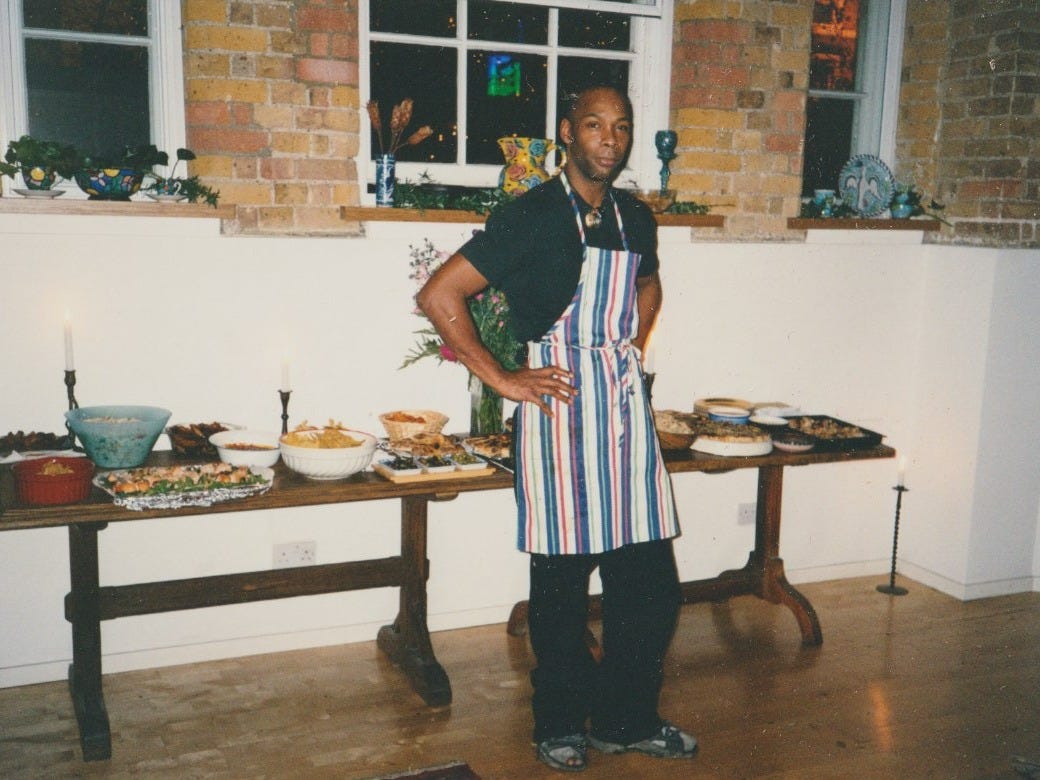

Two weeks later, he helped me move into my new flat. That night, he cooked lamb shanks and mashed potato with a red-onion jus. His mother had taught him to cook as a small child. His years in France had refined his palate and his cuisine was impeccable. After we met, he trained as a chef. He laughed at my slap-dash cooking and did the food for all my parties.

When I took over as director of the Poetry Society, Rob painted the offices, for a fraction of the other quotes and at about four times the speed. He came to events there, too. Once, I was chairing an event on “poetry and gardens”. Rob sauntered in half-way through in his motorbike gear, chains clanking. He sat down, fell asleep and started snoring. I signalled to a colleague to wake him up. She frowned, poked him and he woke up with a juddering snort. When I asked the audience if there were any questions, he stuck his hand up and asked if he could read some poems of his own. I had no idea that he wrote poems. I think I made it clear that he couldn’t.

Once, in the shared garden outside my flat, he put down his glass of wine and opened his arms. He was wearing a purple satin shirt. I still remember the shine of it. “Marry me,” he said.

I didn’t reply.

I have thought many, many, many times about that moment and my silence.

Some months later, he came round to my flat. “I met a woman at a party,” he said. I felt my stomach lurch and sink to the bottom of a deep, deep well. “I’m pleased for you,” I said.

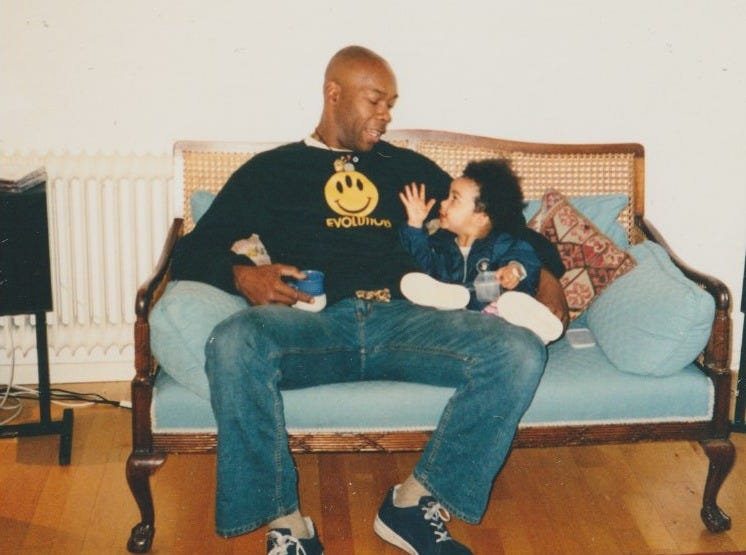

Their daughter was born on the day of my father’s funeral. Two years later, when I was in hospital recovering from an operation, he brought her in to visit me. That tiny girl, toddling around the ward, had her father’s star quality. All eyes turned to her and I wanted people to think she was mine.

Rob lived, with his partner, daughter and then son (when he arrived) about a 20-minute walk from me. He would often pop by, on his way to something or other, for a coffee or a drink. When my sister died, he was there for me. When my father died, he was there for me. When I got cancer, he was there for me and he was there for me when I got cancer again. When I had my mastectomy and DIEP flap reconstruction, and felt as if I had been bisected, it was Rob who picked me up from the hospital in his van. He wrapped me in the furry blanket he used to wrap his children in and did a four-hour round trip to drop me at my mother’s.

Rob came to all my parties. When I was invited to a Buckingham Palace Garden Party, he was my guest. When he told me that he was leaving London, because the mother of his children (and by now ex-partner) was moving to Salford, and that he needed to be near them, I felt as if he had told me he was moving to Mars.

He had been my rock. From the day I met him, Rob was my rock.

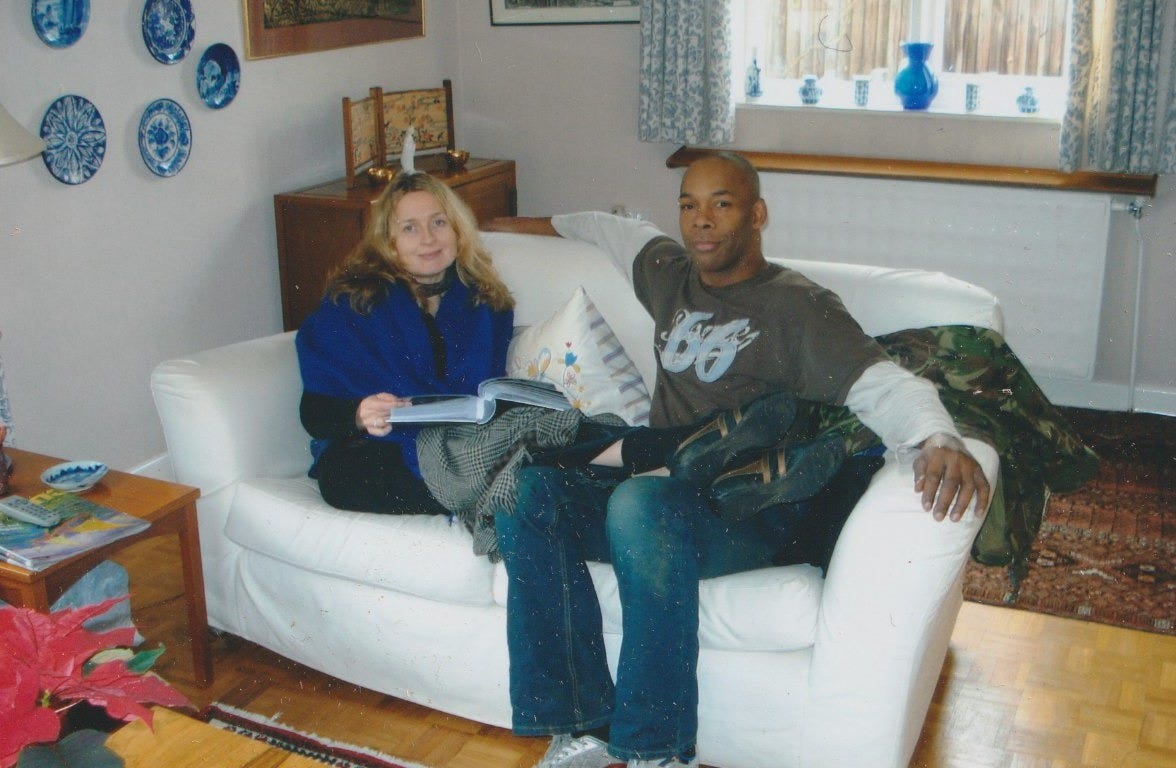

I still saw him, when he was in London. He would often kip on my sofa or stay a night or two at my flat when I was away. When I got a book deal, to write The Art of Not Falling Apart, I interviewed him. Rob certainly knew a thing or two about not falling apart when life goes wrong.

He had, for example, broken his back twice. The first time was when he was helping to rewire a squat for a friend. He was on the roof. He stood up, felt dizzy and fell over the edge. “It was almost like a cartoon falling,” he told me. I smiled when he told me that. I would sometimes come back from buying a pint of milk and find him stretched out on the sofa watching Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles or Superman. He went through the glass mezzanine and landed on a purple coffin. He had had the coffin made by a friend who worked at an undertaker’s, to store his drum stands, and was keeping it at his friend’s squat.

The doctors told him he might not walk again. They didn’t know Rob.

“I was busting for the toilet,” he told me, “and there wasn’t a nurse around. I just thought ‘right, I’m off’. I’m either going to shit or piss myself, excuse my French, or force myself to go and do this. I remember it took me about five minutes to get up and get out of bed. It took me ages to get to the toilet and nobody noticed.”

What followed was like a scene from the Bible. “Oh my God! Nurse! Get the doctor! He’s walking!” Was it agony, I asked him? “Oh yeah.”

It took about a year and a half for him to make something like a full recovery. Three years later, he broke his back again. He’d just got a motorbike, “really nice, a 750”. He was dispatch riding and had just been to visit his mum. He was at the Elephant and Castle roundabout, opposite the rice and peas stall where we met. A car slammed into the back of his bike and sent Rob flying into the metal barrier. He got a fractured neck, a broken collar bone, a broken jaw and lost five teeth. He was in and out of consciousness for days. This time, the recovery took nine months.

The night I met Rob, he lay down on the floor of my flat and asked me to walk on his back. He needed me to click a bone back in place. He had, he told me years later, semi-permanent sciatica. He never complained. “What’s the point?” he said. “There are other people who’ve got much more serious things than I have. I’m up and alive.”

Rob joined the Territorial Army when he was 36. First the Paras, then the Royal Artillery Company and then back to the Paras. He got his “wings” just before my 47th birthday. I remember, because he was doing the food for my party when he went to pick them up. Seared beef and poached salmon.

Two years later, he had a stroke. He had just cooked himself a nice breakfast and woke up to find himself slumped over the table. “My eye had gone,” he told me, “my lip and nose and this and that. I thought, ‘Who the hell come and kicked the shit out of me?’”

Rob developed epilepsy as a result of the stroke. “To be honest,” he said, “the epilepsy was really annoying. I’ve had fits when I’m sleeping, fits when I’m awake. I don’t really care to count them. You just get on with it.”

I asked him if he honestly never felt sorry for himself. “Nah,” he said. “It’s pointless. You’ve got a hand and that’s what you’ve got. You’ve got to go out and pick the aces.”

Rob came down to London for the book launch, at Dr Johnson’s house, of The Art of Not Falling Apart. Most people were dressed casually, but he was in black tie. All eyes turned to him, as they always did. I knew it was painful for him to walk, but he hid it. I had a migraine and had to rush to the loo to throw up after my speech. We both spent the next day slumped on my sofa.

He didn’t make my last book launch. He had a fit and woke up when it was over.

On Tuesday, I heard that he was dead.

I do not have the words. I do not have the words.

In his one of his recent messages, Rob said he had started doing volunteer work with the homeless. His last message was about a gig at a pub at the end of our road. He said he was planning to come and see us “soon/ish”, that the world was currently “nuts”, but that he was “glad to be alive”.

I wish I could tell him one last time what he meant to me. I wish I could tell him what I learnt from him. I wish I could tell him that he changed my thinking and that he changed me.

So I’m telling you instead.

Robert Jackson, musician, chef, gardener, father, friend, rock. 1965 - 2025

I would love as many people as possible to read about Rob. He will probably not get any kind of public obituary, so I would be really grateful if you would share or re-stack this.

What a beautiful homage to a special man who made a profound impact. There are so many ways people touch our lives, and often the most powerful ones go unrecognized, except in the warmth of how they made us feel and memories we have of how they anchored us to what really matters. The way he showed up for you many times (and you, him), how you write he went out of his way to pick you up from your surgery and wrap you in the blanket brought me to tears.

I’ve had the privilege of knowing a few men cut from the same cloth as your Rob. How special to have a connection through all those life phases and be a witness and presence for each other. My sense is you were anam cara, transcending ordinary friendship. I am sorry for your loss. Life is fragile and fleeting, and yet we are so fortunate to spend some moments with those rare souls who are as solid as your Rob.

From one ‘South Londoner’ to another: Rob was a man that I immediately connected with and felt great affection and fondness.

A shared heritage of growing up in ‘Sarf London’ brought with it an understanding of where we had come from.

But what was abundantly clear to all, and particularly with your tribute, not everyone knew where he was going and constantly surprised you with the twists and turns of his life travels.

I’ve just spent the morning walking another dear friend’s hounds on the hill at Rottingdean; listening to the Larks ascending and lifting their voices to the sky and thinking of Rob.

He was a man who charted his own course: safe journey Rob.

Love Nick.